Ten years ago today, the United Nations General Assembly officially recognised the human right to Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) and to mark the anniversary, WaterAid has commissioned 10 visual artists from across the Global South, including Nigeria, to interpret the far-reaching impact access to clean water and decent sanitation has on people’s lives and the role these vital basics play in the realisation of other human rights.

The thought-provoking collection is being released on 28 July 2020 to mark 10 years since water and sanitation were recognised by the United Nations General Assembly as vital human rights, which should be afforded to every person.

Over the last 10 years, millions have gained access to clean water and decent toilets and close to half of the world’s developing countries have amended their constitutions to include water and sanitation as human rights. But there is still a long way to go as millions of people are still being forced to live without access to these basic services due not only to a lack of resources and technologies, but also the inequitable power relations that exist in our world.

Globally, 785 million, that’s 1 in 10 people, still lack access to clean water close to home and 2 billion – 1 in 4 people – don’t have a decent toilet of their own. In Nigeria, about 60 million people (30%) lack access to basic water supply services, about 100 million (54%) lack basic sanitation and about 150 million people (84%) lack basic handwashing facilities with soap and water.

Worse still, well over 70,000 children under 5 die every year from diseases caused by the nation’s poor levels of access to clean water, decent toilets and good hygiene services. Furthermore, only 14% of schools, 7% of health facilities and 14% of motor parks and markets in the country have combined basic water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) facilities. Levels of access to water, sanitation and hygiene service in rural communities are even more worrisome, making this segment of the population far more vulnerable.

International charity WaterAid is using the striking new images to highlight its call on governments around the world to double their investments in providing clean water and good hygiene to those most at need. The call, which takes on a renewed urgency in response to the COVID-19 crisis, is aimed at helping improve the health and prosperity of whole communities.

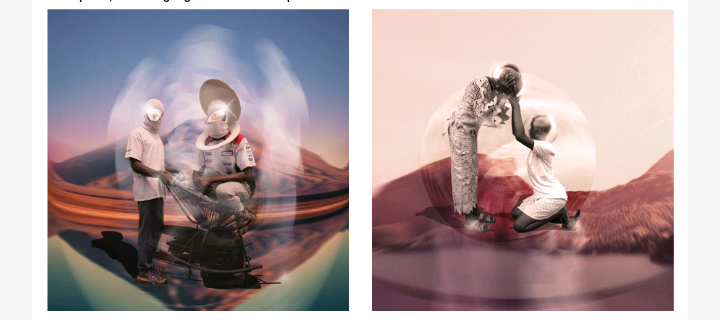

Multimedia artist Joseph Obanubi, who is based in Lagos, Nigeria, chose to focus on the impact a lack of access to clean water can have on women and girls, who are responsible for water collection in eight out of ten households with water off premises. Joseph also created a second piece, which highlights the risks of open defecation:

“For many communities, water sources are usually far from their homes, and it typically falls to women and girls to spend much of their time and energy fetching water, a task which often exposes them to attack from men and even wild animals. Without improved sanitation – a facility that safely separates human waste from human contact – people have no choice but to use inadequate communal latrines or to practise open defecation. Finding a place to go to the toilet outside, often having to wait until the cover of darkness, can leave them vulnerable to abuse and sexual assault.

“[The work] dabbles into spirituality, functionality and gender, referencing Nigerian-Yoruba sitting sculptures with the poses. It dwells on the healing qualities of water as an integral part of a thing. Water is a basic element of life and an essential factor in the Yoruba religion. Yoruba believe water to be a symbol of force and strength.”

Dafe Oboro, also based in Lagos, documents the city’s youth communities through film and photography. Dafe has created a piece which focuses on the daily ritual of bathing, and his image depicts an abundance of clean water.

“Pour me Water, Pure Water presents one idea – bathing as an essential everyday ritual. This serves as a tribute to local workers around me here in Lagos, from the mechanics to the plumbers and the bricklayers who I see taking their baths, with their shorts on, behind parked buses.

It is evident that without such right, a ritual as simple and important as bathing would be impossible. In the end, water is life.”

Serge Attukwei Clottey is a Ghanaian artist who works within installation, performance, photography and sculpture, using found and recycled everyday objects. He produced an image using the yellow plastic jerry cans people use for collecting water in Ghana, where 1 in 5 lack access to clean water. He is passionate about exploring attitudes to climate change in Ghana. He explained:

“In Ghana, the streets are filled with children carrying yellow buckets on their heads, on their way to a fountain…. Every day I would see women and children pour in by the hundreds.

“I want this photo to demand social justice by exposing environmental problems in today’s society. It inspires the human spirit by calling people to action.”

Collin Sekajugo is a Ugandan multidisciplinary artist living and working in Rwanda and Uganda and has created a piece titled All on Her. He described his piece, which depicts a young woman carrying jerry cans:

“I have always found the jerry can to be such a symbolic item in African homes. In almost every community it’s used for trading consumer commodities… most importantly it’s commonly used for fetching and storing water. I have grown to believe that a home without a jerry can is unliveable.

“This artwork speaks to the symbolism of a jerry can versus its importance in accessing clean water and observing sanitation.

“[It] is dedicated to all the women and children – especially young girls – who, on a daily basis, walk miles in search for clean water to sustain their families’ wellbeing.”

Also featuring in WaterAid’s collection are:

Saidou Dicko – a self-taught visual artist, photographer, videographer, installer and painter from Burkina Faso; Henry J Kamara – a British Sierra Leonean artist, photographer and story teller whose works tries to understand what it means to be an African in the diaspora; Cristina de Middel – a Spanish documentary photographer who lives in Bahia, Brazil; Poulomi Basu – an Indian transmedia artist, photographer, activist and author; British- Mexican multidisciplinary visual artist, Monica Alcazar-Duarte and Giya Makondo-Wills, a British-South African documentary photographer selected as one of ’31 women to watch out for’ by the British Journal of Photography.

Clean water and decent toilets are essential to the realisation of all human rights. Without access to these basic services, human potential is limited and extreme poverty cannot be eradicated.

Failing to meet this basic need and human right is both the cause and consequence of some of the world’s most entrenched gender, economic and disability-based inequalities:

In many countries, women and girls are disproportionately burdened with water collection, which means they have less time for education or to make a better living for themselves, trapping them into poverty.

The need for more water during the COVID-19 (‘coronavirus’) pandemic and in the long run because of climate-related water stress risks may make these inequalities even worse.

Poor people and discriminated groups with limited access to basic services are the least able to practice good hand hygiene and protect themselves from COVID-19

Dirty water causes children to miss school due to diarrhoea, an attendance problem that is compounded for girls if their school does not have a facility for safe and decent menstruation hygiene.

Globally, one in four healthcare facilities lack basic water services, and one in five have no sanitation service, exposing mothers, young children and healthcare workers (many of them women) to life-threatening health risks and infections.

People with disabilities are still too often ignored when it comes to access to basic services, including water and sanitation.

Achieving universal access to these basic services goes beyond building taps and toilets. It depends on identifying the inequalities, making people aware of their rights and empowering theme to claim these rights. It is about working together with communities, governments and local partners to make access to water, sanitation and hygiene inclusive – and therefore truly universal.

Applying the human rights principles – equality and non-discrimination, participation, transparency, accountability and sustainability – deepens water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) responses to COVID-19, helping to both protect everyone now and build more equitable and sustainable societies.

Nigeria has made some progress in the 10 years since water and sanitation were declared as human rights – 70% now have access to basic water supply services and 46% to basic sanitation compared to 58% and 32% respectively 10 years ago. However, our leaders can and must do more; and we are calling on the Nigerian government to take action NOW and DOUBLE their current investments in providing clean water and decent hygiene to those most at need. The time to act is now. Together, we need to make sure that everyone, everywhere has these basic essentials. Not just during this devastating outbreak, but long into the future.